- Home

- Halina Rubin

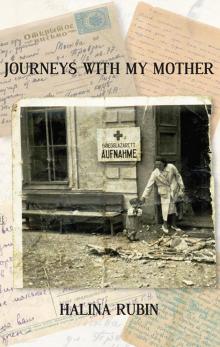

Journeys with My Mother Page 10

Journeys with My Mother Read online

Page 10

On the last Sunday of June 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union, my father was still asleep. The sound of shattered glass and gusts of air woke him. Disoriented, still in his pyjama shorts, he went outside to investigate. It was barely dawn but he could make out planes flying low over the city. He soon realised that these were not military exercises; the planes were dropping bombs. The ground trembled and columns of smoke rose up towards the sky. The noise had woken me too and now Władek had a distressed child to comfort while waiting for Ola to return from work.

She came home from her night shift much later than expected, tired and upset. The hospital was in a state of chaos: blasts had torn out the windows of the operating theatre, meanwhile, the first of the wounded soldiers began to arrive. Their numbers grew throughout the day and soon they had to be placed on the floors, side by side. Some were redirected to nearby schools and offices. The medical staff were not prepared for such a catastrophe; they had difficulty keeping up with essential care.

Over a hurried breakfast, Ola and Władek discussed what to do. Ola had to return to the hospital so Władek walked her up to the park. At midday, Russian foreign affairs minister Molotov spoke on the radio, addressing the nation. Everyone stopped to listen. His voice, booming from the street loudspeakers, sounded uncertain but every word was important:

‘Today at four in the morning, without a declaration of war, the Germans fell on our country, attacked our frontiers in many places, and bombed our cities … an act of treachery unprecedented in the history of civilized nations … The Red Army and the Fleet, and the valiant falcons of the Red Air Force will drive back the aggressor … the whole country will wage a victorious Patriotic War for our beloved country, for honour and liberty. Our cause is just. The enemy will be beaten. Victory will be ours.’

Ewa’s husband Leon came to see Władek. He was in a hurry and would not come in. Both stood at the threshold, discussing their arrangements. Leon’s plan was to leave the moment he and Ewa were ready.

It was already dark when Ola came home again. She stretched out for a few hours, trying to sleep before returning to the hospital. Father went to bed fully dressed, just in case. The night was quiet but sleep would not come as he tried to work out what to do. In the morning he went to work, as usual. His job was to manage one of the cinemas in town. I wish I’d asked him the name of it. Now, of course, I have no idea how to search for it. So I console myself with the insignificance of such a detail. In the scale of things.

I also cannot imagine what prompted him to go to work that day. I wouldn’t have thought that screening schedules or his few administrative duties were top priority. Perhaps he had a sense of responsibility for the property and the people who worked there. In the end, he and his colleagues spent several hours digging trenches. Again.

He remembered it all from Warsaw: the panic and food hoarding, the random movement of people desperate for reassurance, the earnest exchange of rumours and bits of odd news, and mutual consolations. In reality, no one knew anything. The most urgent question was whether the city would be defended. There was nothing to cheer him up as he watched local troops and soldiers marching eastward, the tanks and artillery moving noisily away from the advancing front line.

He could only conclude that the Red Army was in retreat. My mother’s hospital was to be evacuated, the wounded transported to the railway station, and Ola was preparing essential medications and instruments.

Władek volunteered to join the hospital staff. Outfitted with a uniform, issued with a revolver as well as a rifle and ammunition, he was immediately ordered to take part in transporting the wounded.

They had just enough time to get home to fetch me, some clothes, linen, photographs. All the chattels were left to the crestfallen Aleksandra. After bidding their tearful goodbyes, they walked through the park for the last time, hurrying towards the train station. It took a few hours to load everything into the carriages. Theirs was the last train in the convoy.

Five days later, on 27 June, the first German motorised units, followed by the infantry, entered Białystok for the second time. On that day, the atrocities began.

The town looked different when my parents lived here, and later, when the ghetto was established. A small ghetto, with a great many people, just across the street from where Annette and I sit drinking tea.

This town remembers the Jews. We take a walk around Jewish Białystok, the ghetto, reading plaques, looking at memorials and photographs. Finding the street where Reginka, Leon and Haneczka lived while in the ghetto is easy, but the house is no longer there. Annette, tears in her eyes, lingers at every corner. I am trying hard to make connections, wishing for something. Instead, I feel numb.

Not far away, there used to be a big synagogue. The photos show a large and imposing edifice, crowned with a Byzantine dome. It was burnt down on the very first day the Germans entered the town, together with one thousand men and boys who’d been herded inside. My parents, Ewa and Leon, all of us, were gone by then, but heavily pregnant Reginka remained alone, only a few streets away from the conflagration. Białystok is a small place, and whatever happened touched them all. There were many fires and more people killed in the following days. The destruction of the city was so extensive that those standing close to the clock tower could see the faraway forests. It must have been gut-wrenching.

Jankiel Szlang, Halina’s maternal great-grandfather

Izaak Leib Bąk, paternal great-grandfather

Henoch Bąk, paternal grandfather

Ola’s birth certificate

Halina’s father’s family, Władek (back left), Różyczka (front right) with siblings and mother (Babcia Luba), c. 1921

Władek (front) on Yarkon River in Palestine, 1926

In Zakroczym, Ola (right), her sister Ewa (front), 1929

Half photo of two sisters, Reginka and Ola, 1929

Władek in 1937

Postcard from Władek’s brother, David, to cousins in Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia, 1940

Letters to Ola from Russian nurses, her wartime companions

Ola and friend, stopping in Paris on the way to Spain, 1937

Ola in Oryol, winter 1942

Ola in Orsha, summer 1943

Władek in Red Army uniform, 1941

Oryol in winter, 1942–3

Display of medical instruments used in the forest in otriad Iskra, Museum in Lida

Halinka and Ola in Lida, after liberation

Letter from a friend in Moscow to Ola, telling her that Władek is alive, 1945

Reunion of Władek with Ola and Halinka, Białystok, August 1945

Halinka and Ola in Białystok, 1945

Marriage certificate of Ola and Władek, 1946

Ola in nurse’s uniform in Lida after liberation

Halinka and Władek in Łódź, 1946

Ola as a medical student in Warsaw, 1949

Ola and Halinka, Safed, Israel, 1973

Ola with one-week-old Annette, January 1978

13

Six Days and Nights

Ahead of them another wrong road,

another wrong bridge

over the river oddly pink.

All around shots are fired, now closer, now afar.

Above – a plane is slowly circling.

Invisibility would be of use

some grey stoniness,

and better still an absence

for a period short or long.

—Wisława Szymborska

The beauty of this part of the world is not breathtaking. The landscape is green and gentle, even ordinary. Flat, if you disregard the slight undulations of the terrain. Large expanses of forest surround cultivated fields; the clear, slow-flowing Niemen River and its tributaries dissect the land and the opalescent swamps alike. Even now, the area is rich in wildlife. Storks, black and white – their presence considered a good omen – live here, as do herons, cranes and owls as well as almost-extinct bison.

Primeval forests, enormous and b

rooding, have long imposed themselves on the local psyche; their dark mythology – populated with unusual creatures, half-human, half-animal – played on people’s fears, nourishing terrifying fables.

This is where operation Barbarossa, the largest invasion in the history of warfare, the blitzkrieg conceived by Hitler, advanced with great speed. And like some mythical colossus, with a mere sweep of his arm, left behind corpses, burned villages and a countryside laid to waste. A four-million strong, well-equipped Wehrmacht army flooded the west flank of the Soviet Union and kept pushing ahead while a torrent of terrified people took to the roads, attempting to outpace it.

We were lucky to have left Białystok with the evacuating hospital; the train compartments, filled with wounded soldiers, were now turned into movable wards. Standing at the open carriage door, inhaling the cool air of the forest, my father – despite the latest news – was composed. He was relieved to be moving away from the advancing German army.

But we were not even close to Wołkowysk when our train, clearly marked with red crosses, was bombed. The noise was horrendous, the train stopped and those capable of movement made it to the surrounding woods. Father snatched me, and in a few leaps reached the group of trees. Dropping to the ground, he shielded me with his body. Only when the planes were gone did he return to the compartment. Ola, though white-faced and shaking, had remained with the patients. Władek felt ashamed of running away, hiding, leaving her on her own.

In the end, there seemed to be no alternative so they made a pact: father would take care of me; Ola of her patients.

Meanwhile, the train had started moving again, but slowly. Soon it was evident that the locomotive was in its last throes. Steam hissed and the machine heaved its last sigh before finally giving up. The speed and comfort of our escape came to an abrupt end. The carriages were full of wounded soldiers, all in need of care and transport. The commandant, walking from one carriage to another, ordered every capable person to take responsibility for a small group of injured. They had to be taken far from the front and delivered safely to the nearest hospital. That was how, entrusted with a group of twenty, Ola and Władek became a two-person rescue team. At such a moment, my presence could not have been the greatest of assets.

The Białystok–Wołkowysk highway ran parallel to the railway line but one could hardly see the road for the flow of people and vehicles. The Red Army was in retreat and civilians, not protected by anyone, had to rely entirely on their wits. Trucks full of soldiers could move only with difficulty as hundreds of people on foot, horse carts and bicycles determinedly pushed on, hardly knowing where to go except forward.

Władek, waving his rifle, pointing at the injured, stood on the road and tried to attract attention. It took a long time but eventually, almost from nowhere, a large empty cart drawn by two large horses appeared and the reluctant driver agreed to take us. We joined the flow of people moving along the road, which alternated between fields of wheat and forest. A woman dressed in something resembling a nightgown, child in her arms, followed the cart, begging Ola to take her.

Under an unclouded June sky, on a road already littered with discarded vehicles, human and animal corpses, and everyday objects people could no longer carry, we were an easy target.

After few kilometres, our driver had had enough. The cart and the horses were not his. Instead of doing our bidding, he left us. Perhaps he reckoned that the road must be the most dangerous place to be and he wanted to live a bit longer. Maybe he went back to his village. When planes appeared in the distance, father abruptly turned the cart off the road, driving us into a haystack; some of the injured scattered around in panic.

That’s where we remained until nightfall before continuing towards Wołkowysk in search of a train, a hospital or food. Anything. It was almost midnight when, accompanied by a roaring noise, the sky was set alight and there was no longer anywhere to hide. We had to change direction again, so father turned the cart into a side road.

Eventually, at dawn, we reached Wołkowysk. It was desolate. There was no traffic, no train, nothing. An empty ZIS, a military truck, happened to stop close to us and a young soldier climbed down from the cabin. He had lost his convoy during the bombardment and had no idea what to do. Join us, suggested father, explaining our predicament. The soldier looked at the group of incapacitated men and helped place them on the truck. The horses, in much worse condition than the people, had to be abandoned; there was nothing to feed them, all my father could do was to pat them.

This is how my father remembered the days of escape:

Initially, we moved as briskly as the crowded road allowed us, in a large horse-pulled wagon, haphazardly loaded with twenty wounded soldiers, along the Białystok–Wołkowysk road. Near Wołkowysk, we left the exhausted horses and transferred the wounded into a military truck.

Traffic jams; frequent bombardments; wrong information about the enemy position; encirclements real and imagined; destroyed bridges; fording of rivers; searches for food for the wounded; three of us, attending to their injuries; the burial of the soldier who, to everyone’s grief, died – all this, like a film, was going through my mind.

Our hope – that in Minsk we would be able to hand in the wounded and find respite – was in vain. On 27 June, we found the capital of Belarus empty of people, still burning and hazy from smoke. Then, on the road between Minsk and Mogilev, the truck broke down and we were trapped by another bombardment.

It took us six days and six nights to reach safety. We eventually succeeded in delivering the injured soldiers to safety, largely through Ola’s efforts. During our stops, while the men rested, she changed dressings, prepared injections, fed and reassured the wounded.

Sometimes my parents argued. Father insisted on moving fast, my mother pleaded with him to slow down, or even to stop, for the wounded needed a rest. I remember how easily Ola cried, but she was made of tough stuff, my mother. As they drove through burned fields, from one destroyed town to another, she scoured the countryside for something to eat. Once, she found a bag of sugar in one hard granite-like block. They broke it into smaller pieces and shared it around. She made sure that the brave soldier behind the wheel always had his fill. His was a difficult task and so much depended on his driving skills. Another time, she spotted an abandoned package containing soldiers’ underwear and shirts; she took it too. It would be bartered later for food whenever we passed a village. Money was merely paper, of no use to anyone.

Sometimes I imagine their small group in the vastness of the landscape, under bombardment, surrounded by fires, always on the alert, striving for safety. I cannot stop thinking how resourceful and dependable, not to say courageous, my parents were. And vulnerable.

There’s an incident I know about from my father’s recollections. My mother did not like to talk about it. One night, when threatening fires forced us to stop, when we were almost certainly surrounded by Germans and it seemed impossible to find a way out, she asked my father to kill us both. I have no memory of this, of being the child who must have been hungry and tired, not to say frightened. If death were delivered from the hands of my father, I would not have known any better.

But my mother knew and loved life. It was only the fear of falling into the hands of the Germans that horrified her more than dying. The possibility of being captured was very real, but killing us was something my father could not do. He was young. It was not in his character to give up. Having a revolver reassured him that dying could wait.

In this part of Europe, the German force was not mandated to spare cities or their inhabitants. Their plan was to enslave and eventually erase them.

Sitting in my comfortable home in Melbourne, I watch the German footage taken that week, reporting Wehrmacht’s assault on Mogilev: tanks moving through vast fields of young, almost-ready-to-harvest wheat, spitting fire; half-naked artillery men, hot under the burning sun, incessantly loading and firing, destroying everything in their path. Could a mouse have survived such an inferno?

&n

bsp; Then, something unexpected happened. We were stopped and my father was taken away from us. Here is my father’s voice again:

In the summer of 1941, at a Red Army control point near Mogilev, I said goodbye to my family. I got out of the truck as ordered, leaving my wife, a senior nurse in the Białystok military hospital, in charge. She was to deliver the wounded to a safe place behind the battle lines. I was also saying goodbye to my little daughter … The lorry moved on, my wife and Halinka cried out their last words, waving their hands. The wounded, too, waved: ‘Doswidania, spasibo, tovarish sergeant!21’ Their calls merged with Ola’s plaintive cry: Władkuuu, where will I see you?’ Car horns sounded, indicating a traffic jam that had formed somewhere behind, while the vehicle carrying my people moved further away, finally disappearing behind a cloud of dust.

I was ordered to march fast. Suddenly I was on my own, separated from my family but also from the wounded with whom, during those long six days and nights, I had experienced more than I would over the years in different circumstances.

I still had before my eyes the images of Ola’s hospital filled with the injured in the first days of the war, of our evacuation from Białystok. I had not yet recovered from the terrible bombardment of our medical train and could still hear the orders given to us by the hospital commandant to use every means possible to take the wounded deep into the country.

Around Mogilev everything was surprisingly quiet, which seemed strange after days of turmoil. I spent the night in a barn and in the morning the officer suggested I walk to Mogilev alone; perhaps I would catch up with my wife and child? There was much ordinary human kindness and soldiers’ solidarity in that gesture.

Journeys with My Mother

Journeys with My Mother