- Home

- Halina Rubin

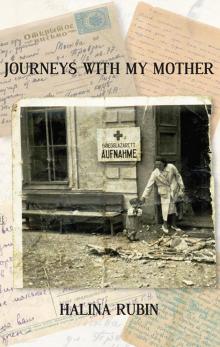

Journeys with My Mother Page 11

Journeys with My Mother Read online

Page 11

The city was full of commotion: shops and restaurants were filled to capacity but there was little to buy. It was still possible to have a modest meal and a beer. Locals and refugees, whole families dragging their bundles, milled around, troubled and anxious.

No one could tell me where to find the military hospitals. What’s more, everyone, including military men and civilians, viewed me with suspicion. It was not surprising. I was strangely dressed: the artillery cap clashed with the infantry insignia on my tunic and high leather boots; furthermore, I was carrying a rifle as well as a revolver.

When I asked for directions to the military hospital, a group of civilians took me to the office of internal security. The interrogating officer was suspicious – I carried my identity papers as well as military documents. He could not reconcile the contradiction of someone in reserve uniform and armed. He screamed and threatened me with execution before consulting someone higher up. In the end, it was decided to disarm me and set me free. I asked him, naively it seems, to give me a receipt for the arms and for someone to help me find the place of recruitment. I didn’t get the receipt but a soldier was assigned to take me there.

The place was in chaos. Everybody was let in and no one let out. Companies and platoons were formed; commandants nominated; party and Komsomol members registered; rifles, ammunition, canned food and dry provisions distributed. Before I knew it, I was incorporated into one of the platoons. A few hours later we were marching in tight columns out of the town.

I craned my neck, hoping to see Ola and Halinka in the crowd of civilians lining the road. Many had tears in their eyes. For them, it was the first week of the war.

Thus, in the end, my mother brought her patients to Mogilev alone. She found the hospital at the railway station. It was already assembled, almost ready to depart. We left the same evening and travelled through the night.

As before, the train was taking us away from the front, deep into Russia, to safety. The compartments were dark, save for a few blue lights, giving them an eerie look. The darkness, the thudding of wheels and the rhythmic movement of the carriages had a soothing effect: most soldiers fell asleep.

Washed and fed for the first time in days, I curled up and went to sleep as well. Ola, her legs aching, stretched out next to me. A multitude of images cluttered her mind and Białystok, left only a few days before, was already a distant past. She missed Władek and felt terribly alone.

The day after, German forces entered Mogilev. We’d escaped just in time.

14

The Short Lives of My Aunts

In sealed box cars travel

Names across the land,

and how far they will travel so,

and will they ever get out,

don’t ask, I won’t say, I don’t know.

The name Nathan strikes fist against wall,

the name Isaak, demented, sings,

the name Sarah calls out for water for

the name Aaron that’s dying of thirst.

Don’t jump while it’s moving, name David.

You’re a name that dooms to defeat,

given to no one, and homeless,

too heavy to bear in this land.

Let your son have a Slavic name,

for here they count hairs on the head,

for here they tell good from evil

By names and eyelid’s shape.

Don’t jump while it’s moving. Your son will be Lech.

Don’t jump while it’s moving. Not time yet.

Don’t jump. The night echoes like laughter

mocking clatter of wheels upon tracks.

A cloud made of people moved over the land,

a big cloud gives a small rain, one tear,

a small rain – one tear, a dry season.

Tracks lead off into black forest.

Cor-rect, cor-rect, clicks the wheel. Glade-less forest.

Cor-rect, cor-rect. Through the forest a convoy of clamours.

Cor-rect, cor-rect. Awakened at night I hear

cor-rect, cor-rect, crash of silence on silence.

—Wisława Szymborska

(Translated by Magnus J. Krynski and Robert A. Maguire)

Ewa and her family followed the same road towards Wołkowysk as we had merely two days before. With them were Leon’s sister Henia, her husband and their two children. All of them left Białystok on a horse-drawn cart. They, too, passed discarded vehicles, scattered corpses and odds and ends that could no longer be carried. They weren’t covering much distance. The surrounding countryside seemed oblivious to their fate. The wheat fields, still two months short of the harvest, must have been, as always, speckled with cornflowers and red poppies; the scent of wildflowers just as overwhelming.

The bombardments continued. After each raid, Ewa attended to the wounded while Leon took care of their daughter Haneczka. Like us, they had to run for cover whenever the planes were heard. Sometimes they were too far from the woods, with not many places to hide. Perhaps it was simply bad luck; perhaps Henia and her baby stood out clearly in the bright field; whatever the cause, a spray of bullets hit tiny Vera, shattering Henia’s arms. Vera died soon after. It was too late; they were surrounded by Germans. Ewa and Leon left the road, and after days of wandering through the countryside, walked back to Białystok. They all did.

When they entered the town they could already see the posters ordering all the Jews to move into the area where the ghetto was to be. In the following days, thousands of Jews, Białystok residents as well as refugees, loaded with bundles of things they could salvage and carry, made their way towards the ghetto. Many women and children walked alone without their men; they had already been killed in the fire of the great synagogue, others executed in the Pietrasze forest. The streets leading to the ghetto were lined with crowds of ill-wishers: silent or abusive. Some grabbed what they could and scuffles broke out. All the while, the Germans recorded the event: filming, taking photographs, preparing documentation for posterity. I look at these images, always searching for familiar faces, in the vain hope of recognising someone.

The ghetto would consist of a few streets where fifty to sixty thousand people were confined. A great many had nowhere to live.

Before their attempted escape, Ewa and Leon lived in Warszawska Street, outside the ghetto area. If not for Reginka who was renting one large room in Nowy Świat Street, they too would have been destitute.

Nowy Świat, which means ‘the New World’, ran through the centre of the ghetto. An optimistic – then ironic – name. In this new world, any Jew, especially a man, was at great risk of losing his life. According to Haneczka, Ewa, wanting to protect Leon, insisted on fetching their possessions from the old address herself. Having secured the help of a Polish man who owned a horse cart, Ewa piled on whatever was of use and walked with him back towards the Jewish ‘new world’.

Finally, towards evening, the lone cart driver and his cargo pulled up in front of Reginka’s place. As he tells it, he was walking next to Ewa when a woman they both knew from work yelled pointing at Ewa: ‘I know her, she is a Communist, a Jewess!’ Ewa was taken away by guards.

I used to imagine her death at the hands of the Gestapo came as swiftly as her indictment. But Haneczka tells me this was unlikely. The quota of the arrested had to be made first, then the prisoners were taken to the forest of Pietrasze. Here, every few days, hundreds of people were executed. I imagine her, my favourite black-haired, dark-eyed aunt, in a thin flowery dress. What else would she have worn on a hot summer day? It’s easier not to think of what was going through her mind in the preceding days and hours.

Annette and I wander around Białystok from one place to another. We are largely guided by Haneczka’s memoir. We come to the parish church. It is very close to the Branicki Park but during the war it almost hugged the periphery of the ghetto. Soulless, neo-Gothic in style, its spires higher than the clock tower, it is too sullen for my liking.

It is summer again and on the large wooden

platform in front of its steps, there is a coloured map of the entire world. Children love it. We, too, take off our shoes and enjoy walking around the world in a few easy steps, counting how many separate Białystok from Melbourne.

We get a measure of the distance between the ghetto and the church – short or long, depending on the circumstances of your walk. It goes without saying: it’s great to be alive now.

It was almost here, when in February 1943, very early one morning, Leon helped his little daughter climb over the ghetto fence. She was told to wait in front of the church till daybreak, then to walk to the house of a Polish couple who were willing to protect her.

Haneczka was a bright child of nine, but standing there alone in the cold proved to be too difficult. Instead of waiting as she’d been told, she resolutely set off. It was still dark and she was attracted to the only place with the lights on. That’s where she stopped, right at the entrance of Schutzpolizei22. Little as she was, it did not take more than a moment for the German guard to notice the only figure in front of him. It was too late to retreat.

She was taken in to be questioned. The interrogation, conducted in German, confused her. When the interpreter was brought in, she failed the simplest of tests, the one that could have given some credence to her claim of being a Catholic. There was not a single Christian child in the entire country who did not know how to make the sign of cross or how to recite ‘Our Father Who Art in Heaven’. Thus, on the day of the first deportation, Haneczka was turned back to the ghetto.

The timing of her return could have hardly been worse; the first deportation was just about to take place. Reginka – who by now had a baby daughter – sought shelter in a German workshop, which offered temporary protection. Leon too had been spared for the time being because of his work outside the ghetto. They were both distressed to see Haneczka, determined to send her away once more, despite her reluctance of being separated from them, unsure about the complicated task ahead. This time, however, she was thoroughly coached on what to do and how to behave. Especially on how to pray.

A few days later, Leon led her out of the ghetto again, all the way to the house where they were expected. Everything went according to plan. Haneczka spent the rest of the war in a village not far from Białystok. She was taken in by a family of farmers as an orphaned Polish child. Before long, she was well-versed in every aspect of the religious customs of the countryside. She thought about her parents, not giving up hope that her mother Ewa was alive, and never forgetting what her father had drilled into her: ‘Remember, you have to live. I’ll fetch you, the moment the war is over. I promise.’

The only image I have of Reginka is that of the frail-looking, timid, twelve-year-old in the photo taken in the summer of 1929 in Zakroczym. I cannot picture her as a grown woman at the age of twenty-six.

Ever since the siege of Warsaw, and later in German-occupied Białystok, Reginka’s life had been a sequence of terrible events. Her husband, whose full name I don’t know, was conscripted into the Red Army when the war began, making it impossible to ever trace him. Since then, pregnant Reginka had lived alone in her room in Nowy Świat while all around her events of unspeakable horror unfolded. When her first and only child, Danusia, was born, she was still living in the ghetto. Two years later, she no longer believed she would live. All she’d wanted was to save her daughter. Everyone wanted to go on living, yet the chances of survival were so few as to be virtually non-existent.

Reginka pleaded with her brother-in-law Leon to save her daughter, but who would hide a small child, so likely to cry, exposing everyone to danger? One would have to know someone outside the ghetto walls, someone who, at great risk to themselves and their family, would be willing to provide false papers, a new identity, a new life. Many people had to be involved to save just one person. Everyday tasks – so trivial in normal times – were fraught with danger. Even the most reliable preparations could end in accidental – or deliberate – betrayal.

In 1943, first Reginka and Danusia, and then shortly after Leon, were forced into the trains to Treblinka. They well knew their destination, and what it meant.

In the locked and tightly packed carriage, Leon, who was separated from Reginka, found a little window. He squeezed through and hurled himself as far from the tracks as his strength allowed him. Though the guards failed to notice, he was battered by the impact. Semi-conscious but alive, he did not dare move until nightfall. Only then did he start back towards Białystok. Somewhere along the way, he knocked on the door of a remote hut. Shocked by his appearance, the woman who opened up let him into her house. She helped him wash off the blood, but too frightened to let him stay, sent him off with some bread. He made his way to the only people he could trust – the same couple who’d helped Haneczka to live outside the ghetto. Despite already hiding two Jewish couples, they did not turn him away. At some stage, there were seven of them in their cellar. This is where Leon remained for several months, until the day Red Army entered the town.

Leon kept his word. Soon after liberation he walked all the way back to the village to claim Haneczka.

Ewa, Leon, Haneczka – one family, three lives, three fates.

Reginka and two-year-old Danusia ended their journey in Treblinka. Of the three sisters who’d fled Warsaw, only my mother lived. The two who’d remained in Warsaw, Tosia and Mania, did not survive either.

15

Oryol

We only know ourselves as much as we are tested.

—Wisława Szymborska

To follow my parents’ movements is to learn geography. I have been always fond of maps, so I was thrilled to find one of the whole of eastern Europe: Poland, Belorussia, down to Romania and Russia all the way to the Ural Mountains – all of it in one big spread.

In early July 1941, a Russian town of Oryol was to be our destination. Situated 350 kilometres south of Moscow at the major railway junction, tucked behind the front lines, it promised to be an ideal location for a military hospital.

Our train journey from Mogilev to Oryol was erratic. At times, without any apparent reason, the train would come to a halt in an empty field, only to pass many stations without so much as slowing, ignoring the plight of civilians. In their multitudes, people spilled out of the small railway stations, crowding near the tracks, drinking tea or simply kipiatok, piping hot water, hoping that the next train would stop so they could squeeze into the already crammed wagons. Priority was given to troops, weapons and military equipment, all moving towards the battlefields, while entire factories from eastern Russia were sent to Ural, Chelyabinsk, Magnitogorsk or Siberia.

After many delays we arrived in Oryol. It turned out to be an unhurried provincial town of pastel-coloured buildings and orthodox churches. Two rivers ran through it and one of them, Orlik (little eagle), had given the town its name – unless it was the other way round. The town was established by Ivan the Terrible when expanding a small military outpost; a fortress was built to defend Muscovy from the south. Later, the town gained recognition for its literary traditions: Turgenev and several other Russian writers were born or settled here.

Oryol was peaceful. My mother was relieved, glad to be walking along its streets without fear, to see the shops with some goods to sell. The absence of explosions, of which I remember nothing at all, was strange. After all, these were the bleakest days of the war, of a fast-moving German offensive and the Red Army’s unexpected, humiliating retreat. The front was still a long distance away but the transports, full of wounded, continued to arrive, filling the hospital to capacity. The soldiers were in a pitiful state, young and old but mostly young, their injuries appalling. There were so many of them and Ola, not knowing how to get in touch with Władek, looked at every face. Not finding him was a consolation; it made her believe in his good fortune.

As it happened, Władek ran out of luck very quickly. In September, somewhere between the towns of Causy and Yarcevo, after days of retreating, his platoon began to attack. It was then that two bullets went t

hrough his chest. They pierced his lungs, narrowly missing his heart. This was his second injury within two months, but this one was serious and he lost much blood. Someone carried him behind the line of fire and, after a few weeks in Kaluga hospital, he was evacuated further east.

My new map tells me where Kaluga is, and for a moment my heart lurches: how close he was to us! Considering the vastness of Russia, he could have been sent to Oryol.

Kaluga was quite close to the front line and frequently bombarded. Anyone who could not walk had to remain in the ward at the mercy of chance. Had my father believed in God, he would have prayed for salvation as he felt that every bomb was aimed directly at him. Instead, after several days, he was taken by train to Kazan, in Tatarstan. This is where he remained until the end of the year. Long enough to start flirting with nurses. The transfer saved his life.

In Oryol, towards the end of September, the sound of artillery fire – muffled at first – became unbearable. The ground shook, sending everyone into a state of panic. The wards were in disarray, reeking of blood and disinfectant as neither doctors nor nurses could keep up with the increasing number of casualties. A great many were diverted to nearby Mtsensk. Thousands of new refugees hit the road. Three days later, the city’s defence was over.

The assault was unexpected and fast; it was too late for our large hospital to be evacuated.

While the battle for Oryol was fought, some patients were placed in the cellars and my mother and I stayed with them. When all went quiet, Ola emerged to see what was going on. The streets were empty, only fires gave a faint colour to the morning sky. The last of the military convoys sped towards Mtsensk and a few civilians scurried for cover.

Journeys with My Mother

Journeys with My Mother