- Home

- Halina Rubin

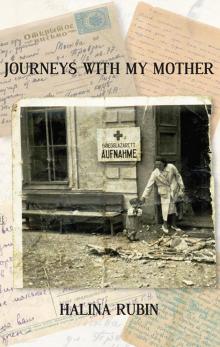

Journeys with My Mother Page 9

Journeys with My Mother Read online

Page 9

Both the Jews and the Poles felt the terror of occupation. For a short time, there were no specific orders concerning Jews. This was as good as giving a green light to violence. Jews were beaten and humiliated, properties ransacked and destroyed. It was not wise for men to venture out into the streets. Any Jew, regardless of age, could be commanded to perform hard labour, to the accompaniment of beating. They stayed indoors if possible.

Ola watched from the third-floor window facing Nalewki Street. A group of Germans stopped their jeeps in front of the shop across the road. They were not in a hurry, giving sweets to the gawping children before stepping into the store. She could hear their excited voices and laughter as they carried bales of fabric, loading their cars to the brim. It was the beginning of October, the first month of the occupation. Not the worst she would see.

Chapter 11

Some People

Some people are running away from some other people.

In some country, somewhere under the sun,

under some clouds.

—Wisława Szymborska

I try to imagine how abruptly, how without mercy, their world changed. Also, their terrible anxiety.

It was understood that men, Jews and communists in particular, were most at risk. My father met every criterion and it was evident to my mother that it would be best if my father escaped immediately.

At the beginning of October, when the border was yet to be properly established, Władek made his way to Białystok, a Polish town already in the hands of the Soviets. Ironically, since the invasion, the eastern frontier had moved closer to home. He went without us, to test the waters, before my mother and I would follow, before the border would be irrevocably shut. It was relatively simple to make it to the other side, then – or so I suppose.

Day and night, in great haste, thousands of people moved from one side of Poland to another. Many, sufficiently vexed, tapped their foreheads to show those bolting in the opposite direction how reckless they were. Decisions, which could determine life or death, had to be made quickly.

My grandparents, remembering the First World War, the civility of the Germans, felt assured that they could survive another occupation. Religion and life experience had taught them to endure. Besides, someone had to take care of their homes. With Władek away, Ola stayed with Brana and prepared to leave Warsaw. She did not speak Russian, and in the days before our escape her father-in-law, my paternal grandfather, taught her some useful phrases and words, such as please and thank you.

In old fairy tales, a mysterious visitor appears carrying a secret message but also a token, such as a precious ring, to prove his trustworthiness. The signal for our escape was just like that, minus the jewels. In the middle of November, a stranger appeared at the door of our household. This messenger, too, delivered proof of his credibility: my father’s photograph as well as his note. Ola was to leave at once. The man, my father wrote in his firm handwriting, was a reliable person who would take us across the border.

Although my grandmother urged us to leave, and her other children were still in Warsaw, the parting was terribly sad. None of them knew whether this would be the last time they’d embrace each other.

Our train was leaving from the Eastern station on the other side of the river; even getting there was risky. To avoid roving German guards inspecting trams for the presence of Jews, we made our way to the station by horse and cart. Ola put a large woollen shawl around her head and shoulders so that she’d resemble the ubiquitous country women who moved in and out of the capital selling fresh produce. I wish I knew what she took with her. I guess her bag must have been full of baby’s clothes and nappies. What else was there, I wonder. It would have been in her character to squeeze in something luxurious as well, if only for bartering. It was still autumn, but cold. We were hardly alone – all sorts of people, with their packs and bundles, were heading in the same direction.

At the station, the ‘trusted man’ was nowhere in sight. Nor could Ola find her friend Fania, with whom she was to travel. Regardless, Ola decided not to return home.

The filthy, impossibly crowded train progressed with exasperating slowness, stopping frequently. When it eventually arrived at Małkinia, the last station on the German side, the crumpled passengers spilled onto the platform. It was swarming with Germans and their excited German Shepherd dogs. Jews were ordered to step to one side. My mother ignored the command. Instead, she left the station and, without looking back, walked towards the new border crossing in Zaręby Kościelne.

According to my map, the shortest distance to Zaręby Kościelne, as the crow flies, is still at least fourteen kilometres, no matter how I calculate it.

Seventy years later I am here, following the same path my mother took, walking into the darkness. The pack is heavy; I feel the weight of the child in my arms. I cannot follow the crow, nor fly over the forest. It is a long way. I am already tired.

But my mother makes it. The German guards wave us through and, at long last, we are in the demarcation zone: no man’s land. Here, in this neutral territory, thousands of young people, but also families – men with their wives and children, bearded Jews – all with their bundles, wait to be let in. We stand between two conjured lines, negotiated by people of some importance sitting in well-heated rooms. We wait with other people who, like us, have sold everything and own only what they can carry.

On one side of the zone our identity spells death, on the other is the unknown, perhaps a warm place to stay out of danger. What we hope for is peace.

The refugees have to be patient because the Soviets, overwhelmed by the numbers, do not want more displaced people. Meanwhile, in a blizzard of wet snow – it’s already the middle of November – we, and everyone else, wait for something to happen.

Nothing does. Some people have been here for days; the uncertainty is killing them more than the discomfort. People beg, curse and insist but the border guards push them away. Going back is unthinkable. Here, in this zone, people die and some are born, and some carry on as if they are crazy.

I know that such things happen all the time, but usually to some other desperate and poor people. So it is difficult to imagine that all this happened to my mother; it’s even harder to deal with her sorrow.

With nothing to lose, Ola approached the Red Army soldiers, so young they looked as if they should have been at school instead of this icy border crossing. All she could do was show her baby’s face and plead, using recently learned phrases. They worked like a secret password – we were let through.

It was already dark when we crossed to the other side into Soviet territory. Numb from cold, unsure of her destination, Ola kept walking through the snow towards the lights. All she wanted was to find shelter from the wind, to lie down and sleep. She told me that having a baby in her arms made her determined to go on without stopping, to resist sinking into the snow.

We did find shelter for the night. One of the distant lights belonged to a typical peasant’s cottage; its owners, not asleep yet, offered Ola a cup of hot, sweet tea. We slept on simple bedding in the kitchen. The next day a local villager took us in his cart to Białystok, where my father was waiting for us.

12

Reprieve

In 2009, seventy years after the outbreak of the war, my daughter Annette and I are setting off into the past.

Although the taste of 1968 has never quite left me, I have been in and out of Poland countless times. It seems that I have much unfinished business in this part of the world.

Annette, born in Melbourne, has been to Poland before, but gripped by what she now knows, wants to see the places that insinuated themselves into the history of our family. We plan to follow in my mother’s footsteps, tracing her escape from Warsaw to Białystok and then – if we are lucky to get visas – to Belorussia.

We begin our journey at the same station from which my mother had set off so long ago with me in her arms. As the train moves towards Białystok, we watch the flat Mazovian landscape, gr

een at this time of the year. We’re practically hanging out the window, determined not to miss Małkinia, close to where the border used to be, and where my mother had to get off. We wish for the train to go slowly, but it is too fast for us to figure out which way my mother could have taken to Zaręby Kościelne.

It does not take long to travel from Warsaw to Białystok. I know little about the town, which offered us shelter more than once.

Annette and I are not alone here. The spirits of Ola’s two sisters, Ewa and Reginka; their husbands Leon and Sewek; little Haneczka and my parents guide us through the streets of Białystok.

My mother was my first, albeit sketchy, narrator. When talking about the past she would get distressed so her storytelling could be convoluted, meandering around events, places, people. And I had not been a good listener. Perturbed, intent on not missing as much as my mother’s sigh, I could hardly concentrate. Later, however, I would discover how clearly she had, in fact, remembered the events of the past.

I hadn’t expected Białystok to be so pleasant. It has the appeal of a small, unhurried place. Those who remember it from before the war can’t accept the loss of the city they once knew, but we like it at once. The main street widens into a triangle of the Kościuszko Plaza. The street and square are closed to traffic; we stroll and sit in one of the many open-air cafés. Once, when villages and even entire towns could be privately owned, Białystok was the property of Count Branicki; his architectural taste is still in evidence. The Town Hall, built by the count, stands in the middle. Designed to resemble a country manor of the Polish gentry, its baroque clock tower rises well above the other buildings. Here is the heart of the city.

But despite its name, the Town Hall never served as one. Instead, local merchants, mainly Jews, had their stores there. Nowadays it houses a regional museum. Before the war it was largely Jewish; this is where the ghetto was set up.

When Ola and Władek found themselves here, Białystok was already affected by the war: bleak and chaotic. Only months earlier, at the beginning of September, it was invaded by the Germans and, shortly after, the Soviets. Within the space of several days, Polish Białystok had been subject to three political realities.

The seven days of Nazi occupation were devastating. On the day the Wehrmacht entered, everybody went into hiding. The sight of empty streets clearly enraged the Germans as their troops went on a rampage – torching houses, firing randomly into windows, breaking doors. By the end of the first day, hundreds of people had been killed and thousands wounded. A state of emergency was introduced straight away, allowing for the destruction, looting and confiscation of property. Every attempt at resistance was put down by violence. So, when on the eve of Yom Kippur the Germans were seen packing their bags and heading west, the Jews in particular were thankful, believing that a major catastrophe was behind them.

The exchange of occupying forces, a consequence of the same pact that allowed Germany to invade Poland, went without incident. It was the Soviets’ turn to claim their part – at a bargain price. The Soviets were not quite the liberators they claimed to be. Yet, after what the Białystokers had been through, it felt exhilarating to be free of the Germans.

Following the changeover, thousands of refugees descended on Białystok. Despite attempts at border control, the Soviets had difficulty containing the flow, which carried us as well. Within a few months, a quarter of a million people had been added to the city’s population, turning its regular inhabitants into a minority.

Refugees were at a loss what to do with themselves in this new place. Cold, hungry and anxious, they milled around Kościuszko Square, exploring, selling, bartering. Everything was scarce; even bread was difficult to buy. The arrival of the Red Army personnel, with its officers and commissars, administrative officials, their wives and children, all hungry for goods, only magnified the city’s woes. Everybody was looking for a place to stay. There was not a house, not even a corridor, in which refugees did not shelter. People slept and lived in the smallest of spaces – on narrow beds, on the floors of public buildings, in synagogues and churches.

We were lucky. The room my father rented – one of several in a well-kept house – had a separate entrance with a little hall, which soon proved to be useful. Like everything else, it was temporary: a table; a few chairs; one single bed, its innards close to the surface. Two worn-out armchairs, placed front to front, served as my bed until father came by a second-hand cot.

They were glad to be in Białystok, grateful for shelter, when everywhere else in Europe Jews were being turned away at every border. The three of us were together again: life was a gift.

The Soviets brought with them a new system. Setting clocks to Moscow time was the first message: the town was no longer Polish. The names of many streets changed, too. Gone were Piłsudskiego, Sienkiewicza, Jerozolimska, Wersalska, replaced by Soviecka, Lenina, Red Star, Moskievska. Private commerce was eliminated and large factories nationalised; Russian language was imposed on offices, schools, even kindergartens. Every day one would hear of arrests of factory owners and community activists.

Then new problems emerged. Refugees were urged to apply for Soviet identity papers. Those who did not warm to the idea, and there were many, were deported. People were sent deep into Russia for a variety of reasons, and sometimes for no reason at all. The Soviets had never trusted Poles and the deportations were an effective way of dealing with overcrowding. Anyone might have shared such a fate – to be taken without time to pack belongings or say goodbye to relatives, escorted to the train station. Locked in unheated trains, they would travel for days, to be disgorged somewhere in Siberia or Kazakhstan.

This was the fate of my uncle, sixteen-year-old Jerzyk. By the time of his attempted escape from Warsaw, the Soviets had become more vigilant. He was arrested for ‘illegal border crossing’ and sent to Siberia. Everyone dreaded such a possibility; being closer to the border was preferable as common belief was that the war would end soon, perhaps as early as spring, when the Allies would make a move.

Ola and Władek applied for Soviet passports. This option did not make them completely safe as living in the borderland area – which included Białystok – was prohibited. Anyone who defied these regulations could be deported.

The winter of 1940, the first winter of the war, was unusually severe. Queues for bread and other staples were long. People waited for hours in the cold, often to learn that there was nothing left to buy. But despite everything, my parents’ lives resumed, in what then passed for normality. Ola was working again; this time as a senior nurse in the Tenth Military Hospital. Perhaps it was in Paris where she’d first thought of studying nursing, as though she could predict how useful it would be. Soon after her return to Warsaw, she began a two-year course and graduated just in time for the war.

In Białystok, she regained her usual vigour. In the middle of that harsh winter, she took her six-month-old on a slow-moving train to a small place past Mińsk to take part in a skiing competition. The fact that she was not a good skier and was in poor form did not cloud her enthusiasm. It would have been unlike her to let such an opportunity pass her by.

The barely heated school building where we stayed was cold, yet the next day, swaddled in my white cocoon, I was at the racing course among cheering supporters, albeit in someone else’s arms. Ola did not come first; she was just glad to have reached the finish line. She returned home invigorated.

I do not know where we lived while in Białystok, but the hospital where Ola worked was behind the Branicki Palace; her daily route to work led through its park. Although much has changed since the war, Annette and I spend some time around the palace, the Versailles of the north, my parents’ favourite part of the city. We walk through its formal French-style gardens, complete with sculptures; watch the ducks splash in the moats. What we enjoy most is the parkland around the palace’s periphery: shaded and informal. Somewhere here I took my first steps.

Before long, we had an addition to our small househo

ld. Pani Aleksandra slept in the entrance hall, which also doubled as a makeshift kitchen. She was to take care of me while Ola and Władek were at work.

From the very beginning, Ola could not tell if Aleksandra – a countrywoman with an ample bosom, given to wearing a long blue dress under her spacious white apron – was pregnant or simply fat. But on seeing her in severe pain one morning, her suppressed groans coming in regular intervals, Ola had no further doubts. Aleksandra, however, was offended at the mere mention of such a possibility. She, who had nothing to do with men; and no, she did not need any help. Not knowing what to do, my mother, concerned as much about Aleksandra as leaving me with someone in acute pain, gave Władek elementary instructions and, somewhat reluctantly, left for work. Not long after, Aleksandra went into labour. My father placed her in ‘the marital bed’ and went into midwifery mode the best he could. Fortunately, the ambulance arrived in time and, shortly after, a healthy boy increased the population of Białystok even further.

Ola was indignant, affronted by the lack of trust and deception. But the storm died out not long after it had flared. After all, worse things can happen in life than a child’s birth. Even if illegitimate. As long as I can remember, nothing much scandalised my mother. I have always been impressed by her equanimity, her readiness for any eventuality, her acceptance of human follies. I’ve wondered where it came from. Possibly her early work as a midwife made her familiar with women and their problems. She resented the disrespectful, cruel treatment of women by those who presumed to be morally superior.

My father had a much lighter take on this incident. He must have been in his element when he gave the boy his name: Vladimir, in memory of Ilyich Lenin. From then on, there was one more person in our household and Pani Aleksandra looked after the two babies. For a short while, we grew up together, Vladimir and I.

Journeys with My Mother

Journeys with My Mother