- Home

- Halina Rubin

Journeys with My Mother Page 8

Journeys with My Mother Read online

Page 8

In telling me all these details, Ola wanted me to know how much I was wanted. Apparently, I was a planned baby. Some plan. For all Władek’s political astuteness and Ola’s careful calculations, between them, they arrived at a perfect mistiming. When Ola was preparing for motherhood, she should have been preparing for war.

On the very day Ola took herself to the maternity clinic on Żelazna Street – where she’d worked for many years – Stalin signed a pact of nonaggression with Hitler. Poland was divided and a second world war was looming.

My mother was placed in the operating theatre which was no longer in use. There she was, alone, anxious, unnerved by the stomping of the soldiers’ boots hitting the pavement. The odd fragment of a poem kept running through her head:

I can hear a new deluge rising

and the pounding of millions of steps

it is for me to choose

the words, the deeds, and the ways.18

The threat of war hung over Warsaw. Everybody talked about it, thought about it. Everybody hoped that somehow it would not come to the worst, because it was summer, ‘and the summer was beautiful that year’.19 People were still enjoying their holidays or were busy preparing their children for another school year: new books and pencils had to be bought. Also because life can never be put on hold, and because war is impossible to fathom. And yet, there was no end to the speculations; some theories were even calming: that the German army was short on fuel and ammunition, that Hitler was merely posturing and, yes, we were strong and well prepared.

And yet, long strips of paper were glued across every window, for protection against shattering glass; and everybody, especially those who remembered the previous war, was stocking up on essentials. Military authorities commandeered civilians to dig ditches, to set tank traps and to shore up fortifications. My father joined in. A maze of deep trenches appeared in parks, city squares and gardens. Sandbags were stacked against shop windows and those who could afford them bought gas masks.

The usually calm, composed Ola – nicknamed ‘Panzer A’20 for her strength – was frightened. The war could not have come at a worse time. Furthermore, her three long days of labour were excruciatingly painful and distressing.

On the morning of 27 August, Władek came to the hospital early. He wanted to tell Ola the latest, before rushing back to his new duties. I was born later that day, so when he returned to the hospital the following morning, my mother had already planted a little ribbon in my hair. I looked cute. My father held me in his arms and cried, overwhelmed as much by happiness as dread. He had no illusions about the impending war.

In the evening, Ewa came to see her little sister. She gave Ola a long warm bath, a gesture my mother would never forget. Never before had she felt so isolated as then, in this huge, spacious, chrome-gleaming operating theatre. This day should have brought her nothing but happiness. But instead she was alone, preoccupied by the ominous threats outside. Apparently, somewhere in the heart of city, theatres and cinemas were still open, people were going to cafés. But all around Ola, everything was unsettlingly quiet. The blinded windows muted all sound, the streets were blanketed by silence. No one walked without a reason any more. Life was held in suspense.

Her room was full of roses. Afterwards, she could not recall who else had visited her and who’d delivered the flowers. We were still in that hospital room when the war began four days later, when the real bombs started falling on Warsaw, when people were killed, buildings ablaze from incendiary bombs.

A few days later our hospital, too, was on fire. As the flames and smoke spread, screaming terrified women ran out of the wards. Some, in haste, left their babies behind and were now howling for help to retrieve them.

According to family legend, my father carried the two of us out of the burning hospital. As wonderful as this tale is, it is wide of the mark. I am certain he would have tried, had he been there, and had he been able to lift my not-toolight mother and me at the same time. A Herculean task.

As it happened, Ola, torch in hand, holding me tightly, grasped her little case already packed for such an emergency and went out into the street unaided. The descending darkness was illuminated only by searchlights, fires and her torch. Someone directed her to the nearest shelter.

The basement in Twarda Street was packed with people, with still more pouring in all the time. Every new blast brought cries, curses and prayers. It was suffocating, with nowhere to sit down. After a few minutes, Ola left me in someone’s arms and went out in search of something better. ‘You left me with a stranger?’ I ask, risking a joke to ease her pain. But my mother, engrossed in remembering, cannot be diverted or consoled.

She ran upstairs, knocking at doors. One of them opened slightly, enough to reveal a young couple: a man and a woman in advanced pregnancy, the woman’s eyes wide with fear. Ola, short of breath, asked if she and her baby could stay, if only for the rest of the night. She desperately wanted to call home, to let them know we were alive but, receiver in hand, staring at the dialling disk, she could not recall her mother’s phone number. She remained forever grateful to these two strangers who took her in, because they understood her distress and her need for shelter.

Most importantly, she remembered to retrieve me.

Rushing along the dark staircase she collided with someone. It happened to be Władek, his face and clothes covered in grime. He’d been looking for us in the hospital and in here, in Twarda Street. For a short, precious moment they were together, ecstatically happy, so relieved to have found each other. But they could not stay together for long. Ola was in a hurry to pick me up, and Władek to return to the burning hospital. A peaceful night with both adoring parents beatifically leaning over my cradle was not my fate.

My mother and I remained in the same location for three days. Ola had nothing to offer to reciprocate the kindness of the strangers. Instead, as exhausted as she was, she washed the floors in gratitude. Then, at night, once the air alarm had ceased, baby in one arm, pack on her back, Ola began her walk home. She was still very weak and moved slowly through the dust-heavy air. My grandmother’s place was not far but she felt as though she would never reach it. The streets, once so familiar since childhood, looked alien, the grotesquely deformed houses beyond recognition. Afraid of getting lost, she tried to walk in a straight line. Yet everything blocked her progress – the ruins of houses, their innards spilling onto the pavements; shards of glass; bomb craters and dead horses. For all her effort, she did not seem to be moving any closer to her destination. I hope I was not crying.

The relief of getting home in one piece, the joy of being with her family, did not last long. The shelling and bombardments did not stop and Brana’s apartment was full. Jankiel, my great-grandfather, had risked travelling from Grodzisk, believing Warsaw to be a safer place to outlast the danger. At some stage, there must have been ten of us living there. It felt better to be together. Though much was made of the beauty of the new addition to the family – ‘Look at her blue eyes!’ – everybody had something more pressing to do. Ewa was away most of the time. The number of wounded was growing every day and babies still had to be delivered. Only my mother – catatonic, listless, tearful – could not face the reality that was September 1939. She’d used all her strength and will to bring me to safety and could do no more. Even when the air-raid alert sounded and everyone sought shelter in the basement, Ola refused to move. She was still there when Brana’s porcelain trinkets shook and fell, when the roar of explosions was deafening.

Władek tried to bring her back from her stupor, to coax her back to life. Now that she had a child, she had to live. And she did, after a fashion. Some atavistic reflex made her feed me and keep me close, but everything else was done by the others. It was my father who changed and washed my nappies, which I dirtied regardless of the shortage of water and even when there was no water at all.

For a long time I was perplexed by my mother’s narrative, how she was moved almost to tears when telling me how lovingl

y my father had looked after me. Was it because, back then, it was not a man’s job? Only when writing about it have I grasped the logistics of nappy-washing. On some days, water had to be fetched in buckets from one of the few old pumps still in existence; the queues, winding around the block, had to disperse as soon as the alarms whined, only to reform once it was over. Tempers were frayed. Many people lost their lives in these and other queues.

No one wanted to believe the war would last long. Much was invested in international solidarity. Britain and France would come to our aid. Indeed, before long, both countries issued Hitler with an ultimatum: the German army was to withdraw from Poland, or else. When the deadline expired, Neville Chamberlain went to the airwaves to announce to the British people that their country was at war; France followed.

The relief was enormous. Warsaw responded with jubilation. Crowds gathered in front of the embassies of both countries to express their gratitude. For all that, the thanks was premature. Neither France nor Britain engaged in military action. It was merely der Sitzkrieg, drôle de guerre, a phony war. Clearly, we were in it utterly alone.

It was also a time of panic and chaos. On government orders the army, the civic authority, the police, even some fire brigades left the city. What is more, the government itself evacuated. Thousands of people streamed out of Warsaw. The only still-functioning radio station went silent. Every day brought more dead, more wounded; more air-raid victims became homeless. The city, dissected by trenches, its streets blocked by barricades, stopped functioning.

The turnaround happened unexpectedly when mayor Stefan Starzyński was appointed the civilian commissar of Warsaw. The radio station began broadcasting again and, as if salvation could come of it, everyone in the city and everyone in the Nowolipki household – except for me and Haneczka who was six – hung on his every word. After all, this was our only contact with the outside world.

Starzyński – who refused to leave the city – spoke every day, regardless of conditions. His measured tone, his ability to oversee the situation and give directions, had a calming effect. He appealed to everyone and his message was simple: go back to work, restore order to the city.

City authorities would remain in the capital regardless of the situation. Apart from those who were mobilised, no one had the right to abandon their post. A strong contingent of armoured forces were on the outskirts of Warsaw, he told us. We were going to defend ourselves. Every day the radio brought new information and orders: to open shops, to save water, to extinguish fires, to assist the staff in overcrowded hospitals – and to bury the dead. The mood changed, people found their inner reserves and felt stronger; they no longer felt abandoned.

The army fought with success, but by now Warsaw was surrounded on all sides. It seemed impossible to get out of the city alive. For stranded civilians, death came from above. The bombers flew lower than before, dropping bombs and strafing anybody in their path. Nights were accompanied by the rumblings of artillery. One had to be prepared for any emergency – we slept fully dressed. Everything was a problem, demanding determination and courage: queuing for bread, tending to the injured, burying the dead.

In the middle of September, the attacks intensified further; the centre of town was burning. Buildings collapsed heavily, as if by their own volition, trapping hundreds of people. The Royal Palace, the Old City, Sejm (the Parliament House), all lay in ruins – this was as painful as the most personal of losses.

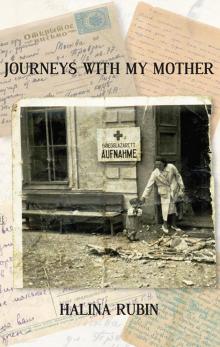

Following international convention, from day one, the hospitals hastily erected signs of the Red Cross, only to be forced to remove them just as fast. Contrary to agreements, they became choice targets. Black, tar-like, acrid smoke hung over Warsaw. There were too many fires for the few fire brigades to keep up; those involved had to deal with them as best they could. The incendiary bombs were a major problem: despite their small size and the minimal damage they caused, they had to be extinguished fast before they would burst into flames.

Every few hours, Władek and his team were rostered for fire duty in our building. It was their responsibility to guide the residents into the basement, to stay on the roof at the ready in case of fire. Once the air-raids were over, the wounded had to be taken to the nearest hospital, sometimes under shelling. Messages had to be delivered, fresh supplies brought. The losses were enormous. Taking bodies to the cemeteries was out of the question so the dead were buried in the streets and city squares; graves sprung up everywhere.

I think of my father, moving from one place to another, doing as much as he could; of my mute mother, distraught and frozen. I wonder – at what stage did she recover and what was it that brought her back to life? The daily entreaties by Starzyński? The example of those around her? Perhaps a call from someone in urgent need of her skills?

Years later, in the first years of peacetime Warsaw, she would still cling to the walls whenever planes flew low. I thought her excessively dramatic. I am ashamed of my insensitivity.

In the midst of these events – when it seemed the situation could not get any worse – there was another calamity. The Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east. It is possible that my parents were not especially troubled by it. While fighting for their city, it was fascism they feared most, and if the Soviets entered part of Poland, who knows, it could have only been for the better. For them, the event was not half as ominous as for most people who knew better than to trust the Soviets. They had no benefit of hindsight, as I do. The secret parts of the agreement between Hitler and Stalin to divide Poland were only revealed after the war.

Towards the end of the month, Hitler, watching fires consuming the city, demanded capitulation. It was rejected and punishment was meted out on the day remembered as Black Monday. Those who lived through it thought it signalled the end of the world, or what hell must be like. Nothing was spared from the relentless assault which lasted all day. Entire streets were on fire – houses, churches, hospitals, schools and markets turned to ruins. That day, ten thousand civilians were killed. From then on, there was no water and no electricity, no gas.

Starzyński spoke to the allies: ‘You are sending us from Paris, from London congratulations and best wishes. We don’t want any. We no longer expect your help. It is too late for that … We seek vengeance.’

Unbelievably, the city – hungry, exhausted, short of ammunition, almost on its knees – continued fighting, and the Germans were still repelled.

Starzyński spoke to the inhabitants of Warsaw for the last time. He said: ‘I had wished for a great Warsaw. My colleagues and I drew up plans for a great city of the future. And Warsaw is great. It came sooner than we thought. And though, where there were meant to be parks, there are barricades; though our libraries and hospitals are burning, Warsaw defending the honour of Poland is at the pinnacle of its greatness and fame.’

Then the radio went silent. That was the biggest loss.

When further fighting could no longer be sustained or justified; when the overwhelmed hospitals could no longer deal with the number of wounded; when the shortage of nurses, doctors and drugs was too great to overcome; the commander of the Polish army settled on an honourable capitulation. The city went quiet.

This was the first month of my life.

The end of the fighting brought instant relief, but already deep inside were other emotions: was all the suffering and sacrifice for nothing? And what now? Bitterness and despair transformed into anger with no immediate way out, so it lay in wait.

Now that it was safe to go out, everyone emerged from the isolation of their homes, impatient to check on relatives and friends, taking in the full panorama of the carnage. They had no choice but to move through the rubble, big chunks of houses, bricks and everyday objects, while the stench of smoke, corpses and excrement still hung in the air. Some people were still buried under the collapsed houses, and the wounded required medical help.

The Germans delayed entry to the city. First the barricades had to be removed and then the streets cleared of debris. From the very beginning, t

he German troops behaved as if they owned the place, displaying the insolence of the conqueror who’d brought the city to ruin. To see the victorious Wehrmacht soldiers – self-assured, well-fed and groomed – was unbearable. The people looked at them with disdain, in silence. Ant-like, they spread throughout the city; their vehicles, tanks and artillery made so much noise, there was no need to look at the spectacle to sense their power. Władek stayed at home.

The terror of occupation was felt quickly. People were shot dead for possessing arms, for breaching the curfew, for answering back. A łapanka was especially feared: German soldiers would suddenly block a street at both ends, trapping men and women who happened to be there; the captives would then be sent to Germany as a labour force.

Within a week electricity and water were back in many parts of the city, but not the radio. Radios had to be taken to assigned depots: owning and listening to one was verboten, on the penalty of death. One of the depots happened to be next door to where we lived. Receipts were duly issued, as if the radios would be returned some time in the future.

On Aleje Ujazdowskie – years later, a boulevard I’d often stroll down with my parents, ignorant of its history – the Germans filmed scenes of bread distribution. There was no shortage of people swarming around, anxious, waiting to get a loaf. Baked by local bakers, made with Polish flour, the bread was thrown into the crowd. But first, the goodwill of the conquerors had to be documented and the people urged to smile. For posterity. As there was nothing to smile about, the scene had to be repeated until it was deemed ‘right’. Bitterness swelled in people’s throats; it was choking. It still is.

Journeys with My Mother

Journeys with My Mother